Soviet Support for the Spanish Republic

| SPANISHSKY.DK 20 JUNE 2017 |

Lecture on Soviet support for the Spanish Republic, delivered as part of the 5th Anti-fascist Harbour Day ‘Wolf Hoffmann’ in Hamburg 29 May 2015

By Friends of the XI International Brigade/Revision and translation editing by Maria Busch

Introduction

As already announced on the 4th Antifa-Hafentagen (‘Antifascist Harbour Days’) last year—on the 70th anniversary of the liberation from fascism—we wish to provide a detailed report on the Soviet support for the Spanish Republic and pay tribute to it.

We wish to highlight the direct military support and the shipping organisation, the transfer of part of the Spanish gold reserves to the U.S.S.R. and thirdly report about the fates of Soviet sailors taken prisoner in Spain by the fascists.

The Soviet military support was substantial. In addition to the direct supply of arms by U.S.S.R., a disguised net of trading agencies outside of U.S.S.R. was set up. They made arms purchases from Skoda Works in Czechoslovakia, for instance, and shipped them on foreign vessels.

More than 2,000 Soviet volunteers fought in Spain, amongst them 772 pilots, 351 tank soldiers and officers, 222 military advisers and instructors, 77 naval officers and sailors, 100 artillerymen, 52 other military specialists, 130 aircraft engineers and technicians, 156 radio operators and 204 translators.

157 Soviet volunteers lost their lives and are buried in Spanish soil.

The gold of the Spanish Republic

A forced transaction?

It is frequently argued that the U.S.S.R. imposed the condition of transferring the Spanish gold reserves for the arms and relief supplies, as if the support was a commercial transaction. This is not true. Already in August 1936, military advisers headed for Spain, and in September 1936 the first ships loaded with tanks, bombers and ammunition set sail for the Republic.

9 September 1936 in London, directly after the meeting of the Non-Intervention Committee, the U.S.S.R. began the logistical planning for the military support of the Republic. The Soviet government had no illusions at all regarding the fascist putsch and further interventions of German and Italian fascists, which would soon prove to be all too true.

On 29 September, at the Politburo meeting of the People’s Commissariat of Defence, a discussion took place on the situation in Spain and a decision was made to implement the covert operation X — the bestowal of active military support for Republican Spain.

At the end of September, loaded with arms the Spanish vessel Campeche left the port of Feodosia heading for Cartagena. Also loaded with arms, the first Soviet vessel the Komsomol sailed 4 October 1936 from the same port and reached Cartagena (port city of the province Murcia, located by the Mediterranean coast) 12 October 1936.

All this took place before a single gram of the Spanish gold reserve was transferred to the U.S.S.R. and no decision was made by the Spanish government to do so.

The transfer of gold

The decision, to transfer parts of the gold reserves of the Bank of Spain to the U.S.S.R., was taken by the Prime Minister, Francisco Largo Caballero, and Minister of Finance, Juan Negrín y López, at the most crucial moment when the fascists’ capture of Madrid was looming. The Spanish government decided on 13 September 1936 to evacuate the 635 tonnes gold reserve and the silver reserve that was stored in Madrid in Bank of Spain. Likewise, 726 tonnes of gold was stored in France on behalf of the Spanish Republic. Additional 174 tonnes of the gold reserve from Madrid, later stored in Cartagena, were transferred to France in September for arms sales.

Over 500 tonnes of gold were transferred into the caves of Cartagena mid-September 1936. However, Cartagena was not a safe place; the Spanish government dispatched a request to the Soviet government asking them for permission to transport the Spanish gold into the U.S.S.R. After consultation, the Soviet government declared that it accepted the request. The declaration of consent arrived at Madrid by 20 October 1936. It read:

Declaration of consent

‘Comrade Rosenberg [Marcel Rosenberg, Soviet ambassador to Spain, red.] is mandated to inform the Spanish government that we are willing to accept the safe-keeping of the gold reserve and that we accept the transport of the gold with our ships returning from the Spanish ports under the condition that the gold will be accompanied by a representative of the Spanish government or the Ministry of Finance and that the responsibility for the intactness of the gold starts with its delivery to the people ́s commissariat of Finance of the U.S.S.R. in our ports.’

Evacuation of the gold

Soon after, about 510 tonnes of gold and other objects of value were evacuated by four soviet vessels via the port of Cartagena to the Black Sea port of Odessa. The first two transports (KIM and Wolgoles) arrived in Odessa by 2 November 1936, the other two (Kuban and Newa) by 4 November. Not only with regard to security, was the operation carried out in utmost secrecy. For the Spanish Central Bank, the gold reserves served as coverage for money supply. Any indiscretion would have had fatal consequences internally as well as externally.

Request for funds and arms

By mid-1938, the gold, which was used for arm purchases, was exhausted. At the request of the Spanish government, the U.S.S.R in December 1938 granted a loan amounting to US $100 million (the equivalence of $1,744.67 million in 2019).

November 1938, Negrin wrote a letter to Stalin and asked for the delivery of more arms on a great scale. This letter was handed over to the Soviet leadership in Moscow by Ignacio Pío Juan Hidalgo de Cisneros y López-Montenegro, supreme commander of the Republican Air Force, at the end of November/ beginning of December 1938.

The scale of the requested arms was immense, and included 600 anti-tank guns, 10,000 light and heavy machine guns, 200 fighter planes, 90 bombers, 250 tanks, six vessels for coastal defence, 12 torpedo boats.

Cisneros was asked by the Soviet Minister of Defence, Woroschilow: ‘Do you want to leave us without arms?’. Stalin and Woroschilow accepted the wish list without limitations and agreed to grant a loan awarded by the Soviet government to the Spanish Republic covering the value of the arms. A guarantee for repayment and collateral for the U.S.S.R. did not exist—the agreement only carried the signature of Cisneros.

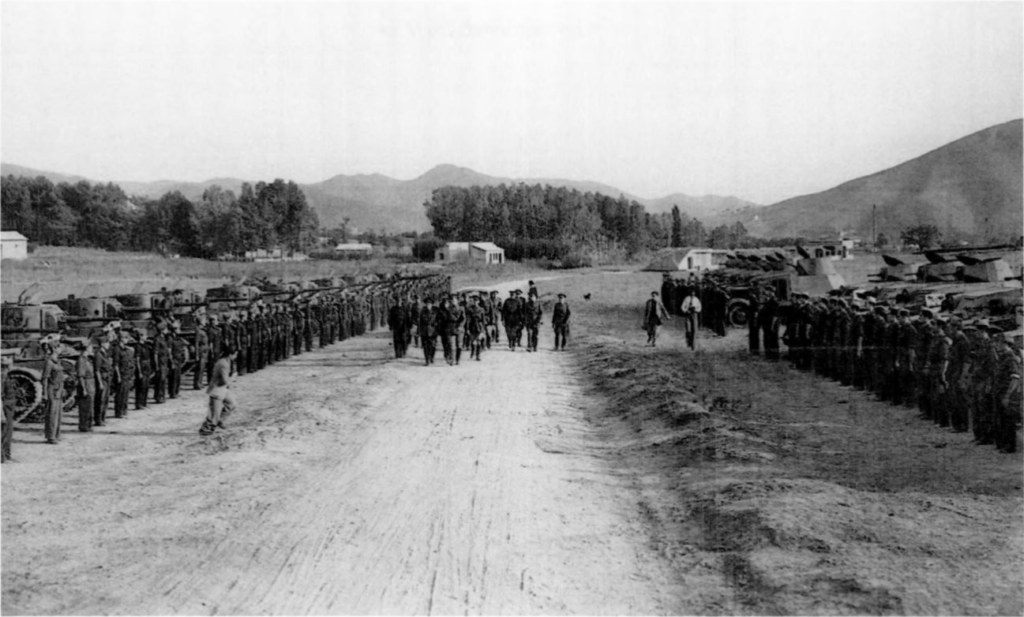

Original caption: Review of Soviet armored fighting vehicles used to equip the Republican Populist Army during the Spanish Civil War

Arms shipment

From 15 December 1938 till 15 February 1939, weapons and military technology were shipped from Murmansk to France.

Cisneros recalls: ‘The military equipment was loaded on seven Soviet vessels entering French ports. When the first two vessels arrived in Bordeaux, the battle was not yet lost and our army would have made good use of the arms. But the French government conceived diverse excuses to delay the transport through France. When the arms arrived in Catalonia, it was already too late. We had no airfields where the aircraft might have been assembled, no territory for defending ourselves. Only if the French government had allowed the delivery of the arms to the Republic immediately after the arrival of the Soviet vessels, would the fate of Catalonia have been different. If we had received the military equipment, we would have had the chance to resist for another few months. Considering the situation developing in Europe, it would have been the collapse of the disastrous realisation of the fascist plans.’

Arms delivery abandoned

On 6 December 1938, Germany and France had signed a declaration of friendship and as a result only a small amount of arms could be transported over the French border. An essential part of the arms had to be returned, and some were destroyed. Early in February 1939, the information that a large part of the Soviet arms had fallen into fascist hands reached the Soviet Union. As a result, the following resolution was issued to Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov, the Soviet Minister of Defence: ‘Comrade Voroschilow. The delivery of arms has to be abandoned. Stalin.’

The circumstances must be enumerated; the Red Army was engaged in heavy battles with the Japanese at Lake Khasan in July/August 1938—only months prior to Cisneros demands. Furthermore, there was of yet no heavy industry or mechanical engineering in the young Soviet Union, which had recently started its transition from a backward agricultural state to an industrial society. Tanks and aircraft could not be mass-produced until 1932—and not entirely professionally at that; some tanks and planes were flawed as a result of an unfortunate shortage of specialised production staff.

In other words, a well-engineered war production did not exist and additionally, the danger of war was looming in the east.

Logistics of the transports

Operations X and Y

As mentioned in the beginning, the elaboration of the planning of the military support started at the beginning of September 1936. It involved the staff of the departments of the Soviet military and political reconnaissance. By 29 September, the plan was presented to the People’s Commissariat of Defence, Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov. In the plan, Spain was administrated under the label ‘X’. A Section X was created and the whole operation of military support was code-named X. The shipping of military equipment was labelled ‘Y’.

In Moscow, there was little doubt that the German and Italian secret services were active on the Pyrenean Peninsula and the English secret service could intervene in the Spanish events.

In total, there were deliveries of arms and personnel at six intervals. The literature enumerates 71 ship voyages.

Operations of this scale must inevitably counter various obstacles and challenges and give rise to a lot of decisions that had to be made.

General Grischin

Among these were the question of who was to be sent to Spain. The choice fell on Yan Karlovich Berzin, the main military advisor to the Republic. He was to head the experienced and highly qualified cadres of military intelligence transferred to Spain. In Spain, Berzin’s code name was General Grischin.

Selection of ports

The selection of the port of embarkation constituted a bit of a dilemma. On the one hand, to guarantee secrecy and to shield the loading of military technique from foreign agents and strangers, the port should be not too large. On the other hand, the port should to have the required depth, port storage capacity and shipping facilities. After some considerations, the choice fell on the Black Sea port Feodosia on the eastern side of the Crimean Island.

However, during the first embarkations it proved to have insufficient shielding and storage capacities. The transports were then to be shipped from the port of Sevastopol on the western side of the Crimea. But here the depth on the pier was insufficient for larger vessels, and more often than not, ships had to be loaded in the roadsteads.

Choice of vessels

A third challenge was the suitability of the ships that were to transport the heavy military technology. Many navy vessels had been sunk during the years of the civil war. At the outset, it was therefore more or less a question of using the vessels available. Amongst them was the Spanish tanker Campeche that departed from the Soviet Union 26 September 1936 (Y1) and the lumber steamship Stary Bolshevik (Y3).

Camouflage

In the earliest delivery of arms, old foreign army surplus was loaded as camouflage. However, the amount of old arms in the total volume of all deliveries was small; only about 60,000 of the 650,000 infantry rifles delivered in 1936 had been produced before 1917.

The military equipment was delivered to the selected Soviet ports in camouflaged wagons marked Vladivostok, thus ensuring that it was officially declared as shipments to the Far East. The tanks did not have own brand labelling and only a few of the airplanes had.

The boxes with arms were addressed to fictive recipients in France, Italy, Germany and Belgium and stored at the very bottom of the cargo hold. The arms were covered with tarpaulins and coverings of timber and on top of this, camouflage loadings of iron ore, grain or coal. These precautions were taken in order to avoid a quick detection of the arms by representatives of the committee for non-intervention or fascist warship inspections. The shipments were duly insured and the ships could embark on a completely ‘official’ voyage.

Maritime transport routes

The highest number of shipments to Spain took place in October-December 1936. During this period, the Black Sea command mobilised 19 vessels with a capacity of between 3,000 and 10,000 tonnes.

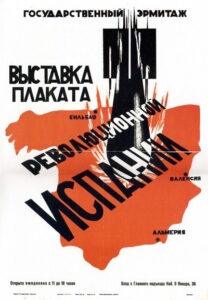

Shipments from the Black Sea ports of Odessa and Sevastopol sailed to the Spanish Mediterranean ports of Cartagena, Alicante, Valencia, and Barcelona. From the Baltic Sea, the vessels sailed to the Biscayan ports of Santander and Bilbao. The vessels entered the ports in fixed order and distance. They did not sail in convoy; near the Spanish coast, the vessels kept a distance of 50 to 62 miles and sailed under cover of night to the port of destination which they tried to reach before sunrise. Identifications of the vessels and flags for navigation were concealed.

Soviet vessel Kursk carrying military supplies for the Spanish Republican Forces in port of Alicante

The voyages

Dangerous maritime waters, patrolled by the fascists, were crossed by night, lights turned off. Guards continuously patrolled bow, stern, port and starboard, searching the horizon for enemy ships. If estimated the situation was not dangerous, the ships headed for the Spanish coast and entered the designated Republican port. As a general rule, the crew unloaded the vessels between sunset and sunrise. The cargo of arms was usually loaded directly onto wagons which left the port for the mainland without interim storage—contrary to official loadings which were carried out by Spanish dockers in the daytime.

During the voyage, the fleet command and vessel were in radio contact twice a day. Information exchange was carried out through a short wave radio transmitter and consisted of short predefined signals. As soon as Soviet vessels (merchant or military transport ships) spotted fascist vessels, they passed on their coordinates by radio to the headquarters, without delay. Thus, the military transport ships could change their routes. The ordinary merchant vessels then pretended it was trying to escape to attract the attention of the enemy vessels. In many cases, the diversion was successful and the battleships were lured away from the military transport ships.

When a normal merchant ship was captured by the fascists and towed into a fascist-controlled port—e.g. Ceuta or Palma—the Soviet ship immediately transmitted a description and the coordinates of the battleship in question to all ships in the Mediterranean Sea, Biscay and the Strait of Gibraltar as well as reporting into which port their own ship had been forced.

The shipments

From 26 September 1936 until 13 March 1937, the total number of shipments was 27: 20 from the Black Sea to Cartagena, two from Leningrad to the northern ports of Spain, one from Murmansk to France and four from other countries.

25 vessels operated arms shipment routes: 11 Soviet, 11 Spanish and three foreign ones. It is believed that aboard all foreign vessels was a Soviet radio man. This was true, in any case, with the Spanish vessel Cabo Palos.

The fourth series of arms transports took place from 21 April until 10 August 1937 with a total of 12 shipments. The fifth series amounted to 14 shipping, among others, by 9 vessels from the company France Navigation. This company was founded on 15 April 1937 by the French Communist Party. From the second series onwards, mainly Spanish and French vessels operated routes.

The sailings of the Komsomol and the fate of the sailors

The Komsomol

The Komsomol was constructed in 1932 in Leningrad; it was the product of the first five-year plan of the Soviet Union and was, of its time, up to standard. In 1936, Georgij Afanasjewitsch Mesenzew became commander of Komsomol. The vessel had been committed to the Black Sea Shipping Company and sailed between Odessa and Leningrad.

In the autumn of 1936, the Komsomol was loading wheat in the port of Odessa. The crew was preparing the vessel for departure.

Taking over the Komsomol

Unexpectedly, the fleet commander came on board and ordered Commander Mesenzew to call off the loading immediately, to unload the wheat and sail to Feodosia straight away. There, he was to take ‘delivery’ of a loading from the People’s Commissariat of Defence. Arriving in Feodosia, the loading of the vessel began: There were trucks, tanks, aeroplanes, ammunition, petrol, food and medicine. The tank crew boarded the Komsomol.

The instructions for commander Mesenzew were: ‘Strict and utmost secrecy ’. The vessel departed without a military escort. Officially, the destination of the Komsomol was Mexico, but it headed for the Spanish coast before reaching Gibraltar.

The accompanying loading documents were not issued. Destination port was Cartagena.

A representative of the People ́s Commissariat addressed the crew and left it up to each of the sailors to stay ashore, no questions asked. Nobody stayed ashore. On 2 October 1936, the vessel set to wave; it was now part of the secret operation X and was labelled ‘Y2’. (As you may remember; the ‘gold question’ was not yet an issue between Spain and the U.S.S.R.).

Arriving in Spain

Off the Spanish coast, the crew detected the cruising, camouflaged German Navy warships the Admiral Graf and the Lützow. When the Komsomol reached Cartagena, Nikolai Gerasimovich Kuznetsov (his code name in Spain was Nikolas. In 1936, he was sent to Spain as a naval attaché) came on board and the unloading started at once.

Even though the unloaded tanks were parked behind a high wall of bricks, the whole town was talking about nothing but this event. The population was jubilating when the tanks appeared in the streets of Cartagena and they shouted: ‘Viva Russia!’ and they threw their berets high into the air. Many thousands had shown up to welcome the ship that brought arms to the Republic.

The tanks transported by the Komsomol were driven by Soviet tank drivers in the initial battle for Madrid where the fascists were fought back outside Madrid.

Fascist reaction

The account of this shipment and its special cargo eventually reached the fascists. They became determined to settle a score with the Komsomol at all costs, wherever, whenever and howsoever. Komsomol‘s journey back to Odessa proceeded without incidents.

The Komsomol’s next trip

Once in Odessa, a new cargo for Alicante and Valencia was loaded: cars, petrol, medicine, food, and presents from the Russian people. This time, the destination port was Valencia.

Also on this occasion, the reception of the vessel was overwhelming; Ten thousands were waiting at the pier and cheering the crew. Almost without exception, every Spaniard threw roses to the crew. From villages far away, peasants visited the ship and brought boxes with mandarins and oranges as presents. The crew tried respectfully to decline, but to no avail.

The Soviet sailors were then invited for a soccer match against a team from Valencia. 80,000 spectators filled the ranks. After the symbolic goal kick by Commander Georgi Afanasjewitsch Mesenzew, the whole stadium was shouting in unison: ‘Viva Russia!’

The Komsomol’s final voyage

And indeed, the following day when the Komsomol set sail off Algiers, it was pursued by the fascist cruiser Canaris. The fascists demanded: –Turn the engines off! They seized the vessel, confiscated the ship’s documents and the sailors’ passports. The crew was ordered to disembark the vessel and was informed that Komsomol would be sunk. 36 crew members left the vessel in their own life boats, just to witness the sinking of their vessel soon after. The crew of Komsomol was then ordered on board the Canaris where they were arrested. The Komsomol crew members were very young. Only five of them were over 36, the commander himself was just 33 years of age.

Not until 20 December 1936, six days after the sinking, the Soviet News Agency TASS could report: ’14 December, a fascist Spanish pirate cruiser set Komsomol on fire and has sunk the ship. Is is yet unclear what has happened to the crew…’

The fate of the crew

After having spent 8 days in the steel casemates of the Canaris cruiser, they were taken to the medieval prison of Puerto Del Santa-Maria in Cadiz at the South coast of Spain. The prison cells were dark, full of rats and other vermin. The time that followed was characterised by incredible deprivations, hunger, cold, brutal and violent interrogations and other indignities. But they could not been broken. They learned to communicate by Morse code through the cell walls. The fascist sentenced the sailors to death and put them in death chambers. They were brought to the prison yard several times, where executions by firing squads were orchestrated. At a later time the fascists read out a declaration announcing that the death penalty sentence was reversed to a jail sentence of 30 years, thanks to the ‘mercy’ of Franco.

It took months before the first sailor was released. After long lasting and tough negotiations between the Soviet government and the International Red Cross, eleven sailors were released. After 10 months, 3 October 1937, they arrived in Paris. One month later, another 18 crew members were released. Three of them asked to stay as volunteers in Spain when they arrived with another vessel of relief supplies in Valencia. They fought in the XII. International Brigade. Their names were: Wassilij Titarenko, Wladimir Podgorezki and Wladimir Fomin.

The last 7 sailors from the Komsomol had to hold out for two years and eight months in the fascist torture chambers. The Soviet government succeeded to get them released in exchange for imprisoned Italians.

Vessels seized or sunk

Besides the Komsomol, the Canaris torpedoed the Soviet merchant vessel Blagojev. The Italian destroyer Turbinesank the Soviet merchant vessel Timiryazev.

Many Soviet merchant vessels were seized by the fascists: the Smidovich, the Lensovet, the Postyshev, the Zjurupa, the Maxim Gorki, the Max Hoeltz and the Katayama, to name a few.

Commander Michail Konoschenko and his crew from the Soviet merchant vessel Smidovich were sentenced by a fascist court to 13 years in jail. He served six months in the prison of San Sebastian near Santander and another 19 months in the prison of Toulouse.

Not until July 1938, the crew could be exchanged for captured fascists.

For further information:

“ЧП – Чрезвычайное происшествие” (“E.A. Extraordinary Accident“), Soviet film from 1958 about the seizure of the Soviet tank Tuapse in 1954.

Mesenzew, Kapitän G. A.: „Die letzter Fahrt der “Komsomol“ and „Unter der Flagge der Spanischen Republik“.

Viñas, Ángel: „Das spanische Gold während des Bürgerkrieges“.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.