The Danish-German Resistance during World War 2

| SPANISHSKY.DK 31 MAY 2020 |

Text excerpt about the Danish-German resistance in World War II from a series of articles about the resistance fight of the Wasserkante (Waterside, Northern Germany) from the Hamburger Volkszeitung, July to October 1947, Ernst-Thälmann-Memorial Hamburg

By Alfred Drögemöller/Translation (from German) by Friends of the XI International Brigade

Perplexity in Gestapo’s Danish Headquarters

The small nation of Denmark is home to a Danish people, whose attitude did not correspond at all to the ‘heroic ideal’ of a boastful and presumptuous ‘National Socialist world view’ and whose love of peace and world-wide tolerance was interpreted as weakness and degradation. It was a nation destined by the Hitler government to play a special role in the war; here a model protectorate was to be created, which would demonstrate to the European peoples the advantages intended for the countries in the Hitlerian ‘New Order of Europe’ in which people were prepared to submit, without resistance, to the wishes and interests of German imperialism. Denmark, however, refused to assume the role as Hitler’s canary.

Brickworks chairman Gunnar Siim assassinated during a dance night in the company of German officers. Photo: The Museum of Danish Resistance (cropped)

Resistance movements were establish and developed, which were a source of astonishment and perplexity to the occupying power; there was not a single company collaborating with the Germans which was not destroyed or crippled, not a day went by without railway lines were blown up by the hundreds and the members of the fifth column, the Danish Nazis and the Gestapo officials risked falling victim to the well-directed bullets of the freedom fighters.

Burmeister & Wain power plant after BOPA’s sabotage 21 December 1943. Photo: The Museum of Danish Resistance

Sabotage of a car transporting fright train on its route between Herning and Airbase Krarup (mid-Jutland) in 1944. Photo: The Museum of Danish Resistance

In the city of Odense, our comrades who managed to tap into the telephone lines of the Gestapo headquarters and intercept their conversations—thus saving several resistance fighters from being arrested—were able to hear with their own ears the trembling fear that had seized these ‘heroes’.

This was an enemy that was invisible yet ever-present, unidentifiable and uncatchable, that penetrated the offices of the German authorities and Wehrmacht [1] commandos, that unexpectedly took action whenever and wherever, that spread insecurity and panic. This was an enemy against which the Gestapo had to succumb.

Connections with the Wehrmacht

Dr. Best—also known in Denmark as the Bloodhound of Paris—and his assistants represented Nazi Germany. Our task could only be to oppose this ‘official Germany’ with the other, the true, the future Germany. We had to act in the name of all those who recognised that Hitler had taken the path of destroying Germany’s national existence. It was a question of the existence or non-existence of a German people. Against this backdrop, our approach could not be based on the interest of the Communist Party, but rather on establishing cooperation with all Germans who were committed to end the war and overthrow the Hitler regime.

Dr. Werner Best and (right) commander-in-chief of the German troops in Denmark, general Hermann von Hanneken. Photo: The Museum of Danish Resistance

In the first few years, it was not easy to establish connections with German soldiers or members of the German colony. The German people’s confidence in victory was still far too strong making the anti-fascists feel so deeply isolated because of their convictions that many of them did not dare to show their true colours or even take our leaflets et al. into the barracks.

In the beginning, we had to distribute the publications rather indiscriminately: on the railways, in restaurants frequented by members of the Wehrmacht, at German airfields, etc.

Addresses of families were systematically collected wherever soldiers came and went. All this had to be done with the utmost caution as a large number of them—especially the younger ones—openly expressed their contempt and indignation about the pamphlets.

A particular difficulty arose from the fact that Denmark was being used by the Wehrmacht as a kind of holiday country visited by army units temporarily withdrawn from the front. Only through tenacious and patient work was it possible to establish a whole series of firm links and regular connections with units of the Wehrmacht staying in the country over a longer period of time.

Officers against Hitler

Our work among the members of the occupying regime received a decisive impetus when the activities became known to the National Committee for a Free Germany, of which General v. Seydlitz was a member. From discussions with a number of officers with anti-fascist inclinations we realised that in these circles it was a particularly acute concern whether they should disregard their code of honor as an officer by breaking the Hitler oath in the knowledge that Hitler’s disastrous policies threatened the existence of the nation.

Friedrich Paulus and Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach (left), Army group B in Stalingrad. Photo: BundesarchivLicense

We decided to issue a special pamphlet (24 pages) on this subject targeted at the officers. The pamphlet included the position and role of Freiherr vom Stein [2], Ernst Moritz Arndts, York [3] et al. during the Wars of Liberation 1812-1813. This pamphlet sparked heated discussions in officer circles, and we had the joy to come across people who had read and been impressed by the pamphlet, even a year later.

2000 newspapers copied and distributed

One day, one of our comrades presented us with an issue of the Deutsche Nachrichten (‘German News’) which we published monthly (later fortnightly). We could not believe our eyes. We were familiar with the content of the newspaper; these articles and calls were written by us. But this issue was not printed by us. It must have been copied and duplicated. Naturally, it occurred to us that the Gestapo might be behind it. It was decided to proceed with extreme caution to establish the origin of this newspaper.

A few days passed, then the comrade in charge reported that the paper had been copied and printed with a circulation of 2,000 copies by a Danish printing company in the city of Aarhus on behalf of a German soldier in the Air Force.

From information obtained through the Danish resistance movement we were able to establish that the Dane in question was legit. Our comrade went to Aarhus and tracked down the German soldier. The man—the son of a Viennese professor—was an Austrian and a businessman imbued with a fervent hatred of the Nazis. He had managed to get hold of that particular issue of the Deutsche Nachrichten by chance and had decided without further ado to take care of the distribution of the newspaper on his own initiative. He had got on the train and, in the course of a few days, distributed the 2,000 newspapers in the cities of Aalborg, Viborg, Horsens, at the Kastrup Airport et al. without being caught.

Interpreters as couriers

Throughout 1944, we were in the fortunate position of being able to reduce our travel activity. Travelling in Denmark was not without danger as trains and stations were subject to strict German control.

One day, while carrying out our activities, we came across two soldiers who spoke excellent Danish. They agreed to serve as ours interpreters and to give lectures about Denmark and the Danish people.

Strangely enough, they were not attached to any specific unit but served directly under the authority of a senior Ministry of Aviation officer. When we asked them why, they smiled and revealed that until a few days ago they had not understood this either, but by now they had received ‘certain orders’ from Berlin to supply ‘certain gentlemen’ with large quantities of Danish butter, bacon, etc.

The German steamer, S/S Heyer, operating a regular food shipping service between Odense and Hamburg, was sabotaged in the Odense Havn (‘Port of Odense’) 31 August 1944. Photo: The Museum of Danish Resistance

We decided that they should, of course, carry out these orders. Living in Denmark free from any control, issuing their own marching orders, these two men, who were Marxist-trained and politically experienced, were of enormous importance to us. We have never had better or even safer couriers.

Before the surrender

In the months preceding the surrender, the Wehrmacht showed signs of strong disintegration. Everywhere among the soldiers discussions ensued as to whether the senseless and criminal war would be fought down to the last man and whether Denmark, too, would become a theatre of war.

Desertion became a widespread phenomenon. Of significance to us, it was now possible to openly distribute leaflets, calling for the removal of the Gestapo and the war prolongers, to the soldiers on the streets without them intervening or resorting to the use of their weapons.

Groups formed within the German garrison at the Kastellet (‘Citadel’) [4] had already been assigned with the task of disarming and arresting the officers in the event of an invasion or uprising by the Danish resistance movement.

Just a few hours after the commander of the Citadel marshalled his troops to proclaim in a speech, “The Citadel is our grave” we were able to hand out leaflets to the soldiers of the Citadel in which the commander was informed that the soldiers of the Citadel refused to share his grave.

There were countless examples of even high-ranking officers having agreed with the illegal Danish resistance movement on a common approach in the event of open fighting. For the past few months, the walls, pillars, et al. have been covered with calls to the soldiers. For weeks, we daily pasted large quantities of a newspaper with the latest news from the war fronts on every available surface. The Free Germany leaflets and newspapers were produced in tens of thousands and—for the most part—distributed openly.

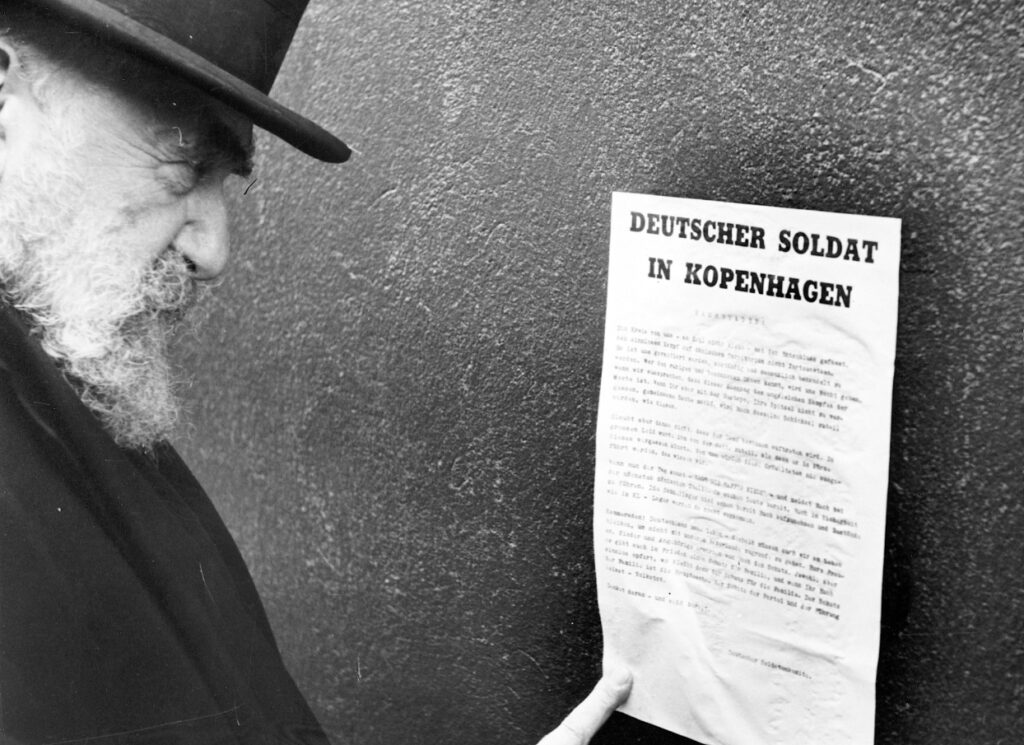

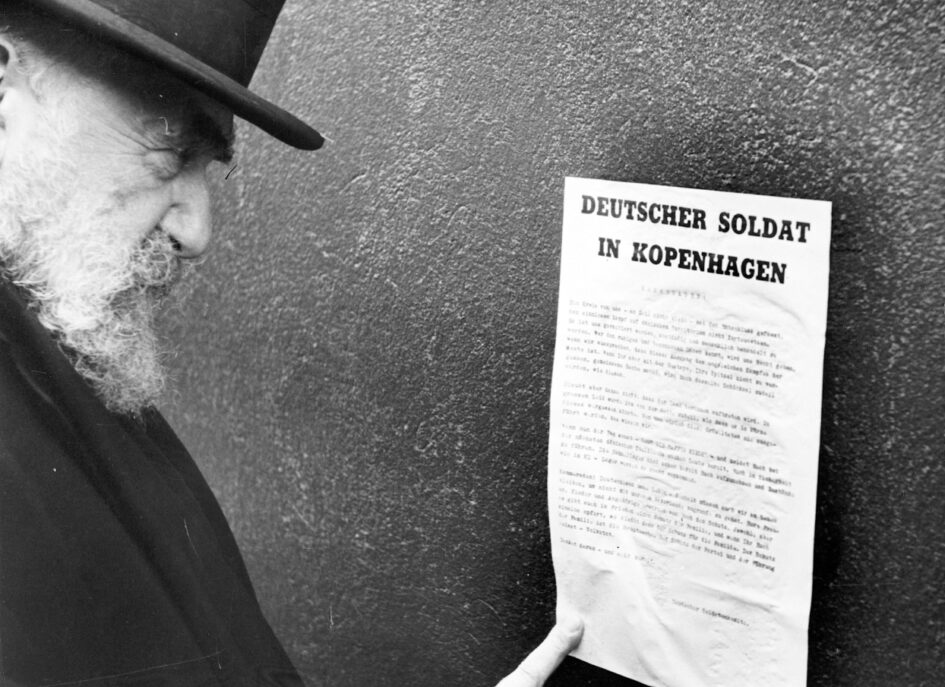

Deutsche Nachrichten: call to German soldiers, pasted on a wall in Copenhagen. Photo: The Museum of Danish Resistance

Steadfast anti-fascists

The German fight against fascism, which was initiated and organised solely by German communists, was waged by courageous and committed men of every social class from Germany and the German colony. It was a fight that claimed its victims.

Special mention should be made of Konrad Blenkle, who was executed in Plötzensee Prison in 1943. Mention should also be made of some of the finest and most capable Communist Party officials: Karl Nieter, who for years frequently traveled to Germany to support the struggle of his comrades; Willi Boller, who was able to stand firm against the Gestapo’s attempts to ‘persuade’ him to reveal the addresses of his comrades.

Not only did the fight of the German anti-fascists in Denmark contribute to the failure of the Nazi criminals to achieve their goal of continuing the fight even after the capitulation. Above all, their resistance and commitment demonstrated to the Danish people that numerous Germans fought against Nazi tyranny, that another Germany existed besides that of Hitler.

Notes:

[1] Wehrmacht was the armed forces of Nazi Germany.

[2] Freiherr vom Stein is an alternate name of Heinrich Friedrich Karl Reichsfreiherr vom und zum Stein.

[3] Probably referring to Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg.

[4] During the occupation of Denmark, the German forces used Kastellet as their headquarters.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.