Notes on the History of The Internationale

|SPANISHSKY.DK 14 APRIL 2019 |

Pierre Degeyter and the workers’ choir La Lyre des Travailleurs

Pierre Chrétier Degeyter was born 8 October 1848 in Gent, Belgium. Around the age of ten, after the family had relocated to France, he started working in the textile mills of Lille. In order to develop his skills, Degeyter attended a night school for workers. He showed early indications of musical talent and from the age of 17, he and his brother Adolphe used to entertain the workers with his own melodies and lyrics and those of others.

When the Franco-Prussian War broke out (1870), Degeyter was enlisted in the French army. Following the collapse of the front, he tried to get through to France, where the Paris Commune had recently been established (18 March 1871). He was, however, arrested by Duke Magenta’s soldier just outside the city and brought to Northern France and later released. How he managed to escape with his life in unknown.

In the following years, Pierre Degeyter worked in the model workshop of the iron foundry Compagnie Fives-Lille in Lille. In those years, the city, marked as it was by a high level of political activity, was a hotbed of workers’ associations of political, informative and entertaining nature.

Among the numerous associations formed during this period, was the workers’ choral society La Lyre des Travailleurs (‘The Workers’ Lyre’). Pierre Degeyter, who was known for his musical skills, was chosen choirmaster. It was, in fact, a political post of considerable importance, when we consider the significance of political songs at this time.

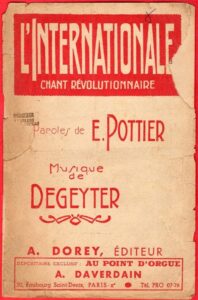

Chants Révolutionnaire

Being a choirmaster, Degeyter was constantly in search of lyrics he could set to music and rehearse with his choir. Gustave Delory, one of the leaders of the French socialist labor party, took an interest in the choir. In 1928, Degeyter told a journalist about what subsequently turned out to be everything but an ordinary evening in the choral society: “One Saturday evening in the summer of 1888, Delory appeared in the The Workers Lyre. As we parted after the rehearsal, Delory approached me and said: “I have a collection of poems by the late Eugene Pottier. Have a look at it, you might find something that works. We do not have a revolution song and you have the skills to write one.”

As soon as I returned home, I took the little book out of my pocket, I happened to open up to the page where a poem titled Internationale started.”

The book was Eugene Pottier’s Chants Révolutionnaire, published in 1887. Delory had obtained it by chance and he immediately recognised that this was something extraordinary that deserved to be known.

The poem Internationale is turned into a song

Throughout that Saturday night (16 June 1888) Degeyter was reading Eugène Edine Pottier’s collection of poems — he was in no doubt. Internationale, which Pottier wrote during the ‘bloody week’ (21-28 May 1871) that marked the downfall of the Paris Commune, was the poem that most poignantly described the realities he was currently facing. That very night, Degeyter wrote a draft of the melody. By turning the opening verse into a refrain, he ended up with a song of six verses rather than the original seven ones. The following day, he completed the music for the refrain.

Monday morning at the iron foundry, a couple of his co-workers and members of ‘The Lyre’ asked Degeyter about the book Delory had given him. Degeyter told them that he had written a song, and they agreed to meet after work in the piano equipped Café Liberty and hear the song.

Monday 18 June 1888 in ‘Liberty’, located on Rue de Vignette, Degeyter sang The Internationale for three foundry workers. His comrades were instantly enthusiastic about the song and it was decided to rehearse the song as soon as possible. The rest of the week, Degeyter rehearsed the song in ‘The Lyre’ and on the night of 23 June, the song premiered at a feast for the workers’ party’s magazine sellers.

The song was a success and the workers’ party branch in Lille decided to print 6,000 flyers of the song. Both lyricist and composer were bylined, however, while Eugène Pottier was credited as lyricist, De Geyter was credited as composer. Perhaps they wanted to ensure the protection of the composer from potential reprisals due to the rebelliousness of the song? We do not know for certain. We do know, however, that the incomplete credit gave future rise to a tragic fratricidal struggle.

(The failure to specify the composer’s first name enabled Pierre’s brother, Adolphe, supported by now mayor Delory, who had turned into a ruthless opportunist, to claim copyright of the music. The legal proceedings that followed ended in Adolphe’s favour. During the First World War, Adolphe committed suicide leaving a letter that revealed that pressured by Delory, who was motivated by the economic advantages deriving from the copyright, had claimed to be the composer of The Internationale. At a new trial, in 1922, Pierre Degeyter was recognised as the legitimate composer. In various publications, the improper name of the composer still appears, embarrassingly so, also in Forlaget Tiden’s (Danish publishing company) version of “Folkets Sangbog” (“The People’s Song Book”) from 1947.

In the history of humanity, this song, born of the meeting between these equally genius and modest workers, is beyond comparison in scope and depth. No other music, no other song has ever reached this level of beauty and significance

Marcel Cachin

If the workers were quick to realise that The Internationale was a song that captured the essence of their conditions and aspirations, the authorities were equally quick to realise the threat it represented to status quo.

In 1894, a teacher by the name of Armand Gosselin released a new version of The Internationale and the government immediately put him on trial accused of encouraging military insubordination (verse five). He was sentenced to a term of imprisonment of one year. This attempt to suppress the song had exactly the opposite effect. The trial against Gosselin intensified the interest in the song. By now, nothing could stop The Internationale.

From official anthem of the French workers to anthem of the international working class

From the 3 to the 8 December 1899 , the first ever joint French socialist congress was held in Paris. Emotions ran high in this assembly representing, as it did, so many different socialistic views. Especially one question provoked contriversies: Should socialists take part in a conservative government?

The dispute originated from socialist Millerand’s appointment to the conservative Waldeck-Rosseau government in which Galliffet, the executioner of the Paris Commune, was Secretary of War. The congress was about to sink into chaos. At the last day of the congress, people in the assembly hall started to shout “The Internationale, The Internationale”. According to the congress minutes, this is what happened: “standard-bearers appear on the stage. Citizen Ghesquière steps onto the stage and starts singing The Internationale. The whole room sings along enthusiastically.” The Internationale had become the official anthem of the French workers.

In 1900, In the first issue of the russian, marxist newspaper Iskra (‘Spark’) the French version of The Internationale was reprinted. In 1902 followed journalist Johan Menander’s Swedish translation which was used in Denmark for a couple of year until 1906, when Lycinka Hansen translated it into Danish. The 1911 Christmas issue of Social-Demokraten (social democratic Danish newspaper) contained Hans Laursens’s Danish translation which is the version we Danes sing today. Check out the English versions here.

Your immortal song has carried your name to the four corners of the world

Pierre Degeyter died 26 October 1932. He was buried at the cemetery in Seine-Saint-Denis followed to his grave by 50,000 people and the tune of The Internationale. The funeral was held by the leader of the French communist party, Marcel Cachin.

We conclude these notes on the history of The Internationale with an excerpt from Cachin’s speech:

“A final salute to the faithful comrade Pierre Degeyter. The old man with the innocent and animated eyes of an artist, whom we, until recently, could meet in the street, belonged to the dynasty of the great people’s bards […]. And one of his compositions reached heights that no other artist can aspire to reach.

When a collection of Eugène Pottier’s poems came into his possession, he chose this particular poem not only because it seemed the best suited to set to music, but because it was charged with the same revolutionary potency and rebellious class consciousness as was Eugène Pottier himself and this still, silent flame.

In the history of humanity, this song, born of the meeting between these equally genius and modest workers, is beyond comparison in scope and depth. No other music, no other song has ever reached this level of beauty and significance.

This man who, in a single inspiring day, has bestowed upon us such mighty weapon and bulwark of unity deserves a heartfelt thanks from the entire international working class.

Pierre Degeyter, faithfull revolutionary, loyal worker without errors and vices, you who modestly got embroiled in unnoticeable cities, almost unknown, you whom faith also granted the taste of human suffering and bitter wrath, rest in peace.

Your name will not be forgotten. Your immortal song has carried it to the four corners of the world.”

This marks the end of our notes on the history of The Internationale, but we have a little surprise for you. Follow the link and scroll down to the video icon. Enjoy!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.