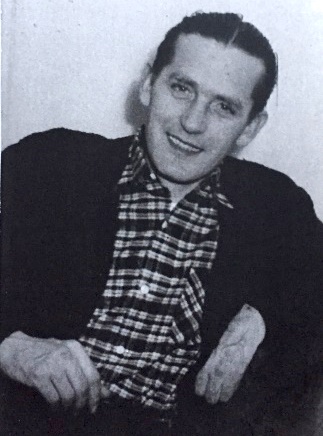

Viggo Christensen Holm

| SPANISHSKY.DK 19 JANUARY 2020 |

Viggo Christensen Holm was one of the approximately 500 Danes who fought in the Spanish Civil War. Like so many of the Danish volunteers, Viggo was a communist and continued the fight against fascism in the Danish resistance

By Allan Christiansen/Translation (from Danish) by Maria Busch

Viggo Christensen Holm was born 10 March 1914 in Ålborg to butcher Alfred Kristensen Holm and Ane Petrine Holm (born Andersen). Viggo was a member of DKU/DKP (the Communist Youth of Denmark/the Danish Communist Party) and worked as a chauffeur. He was married to Jonna Holm (born Andersen) in 1936 and divorced in 1937. They had a son. Viggo was married twice more; to Mrs Holm (born Olsen), with whom he also had a child, and to Mrs Christensen Holm (born Hansen). His latest known address was Peter Bangsvej 237, Vanløse (an administrative district of Copenhagen). Viggo died 12 April 1967 in Copenhagen from cancer, 53 years old. He donated his body to the Department of Anatomy at Copenhagen University.

Viggo Christensen Holm left for Spain 23 April 1938. After arriving, he became part of Battalion Instrución. He was later transferred to the military sanitary service in the predominantly Scandinavian 2 Company Martin Andersen-Nexø in the predominantly German XI IB 2 Battalion Hans Beimler. Along with 91 other volunteers, Viggo returned to Denmark in November 1938.

During the German occupation of Denmark, Viggo Holm was arrested by the Danish Police on the basis of the so-called Communist Law, 2 November 1941 and incarcerated in Vestre Fængsel (‘Western Prison’; a Copenhagen prison used by the Gestapo during the occupation). A couple of months later, he was transferred to Horserødlejren (Horserød internment camp) receiving prisoner number 220.

29 August 1943, Viggo Holm and 91 other comrades escaped from the Horserød internment camp.

He contacted the resistance movement BOPA and until the very end of the war, he participated in the resistance.

Viggo Holm wrote a series of letters to his family and articles for the DKU magazine Fremad (‘Forward’) about the fights and circumstances in Spain. But it is now time for Viggo to tell us about his experiences — he gets right to the point:

THE CROSSING OF THE EBRO THE NIGHT BETWEEN 25 AND 26 JULY 1938

Three months in Batallion Instrución

After 3 months in Batallion Instrucion and having completed a training course in modern warfare, from ‘stopping’ a tank to gunning down aeroplanes and wrapping a bandage, 26 July 1938, I reached the Ebro — the largest river in Spain.

For about six months, this beautiful river has been the frontline, a natural bulwark against the fascists’ further advance towards Catalonia.

As I mentioned, the Ebro is Spain’s largest river — broad and raging, beautifully surrounded by high, steep mountains and banks and lush vegetation. According to foreign ‘expert’ opinion, it was impregnable, which explains the poor fascist defence of the opposite riverbank. They didn’t expect us to attempt to cross the river, and it was a serious oversight that would prove very costly.

One night, the night of 25 and 26 July, we crossed the river driving the fascists’ and experts’ opinions to hell.

Well, we didn’t know that in Batallion Instrucion, though we expected as much, since we had done nothing for the last few weeks but rehearsing how to cross a river. From our experience, the People’s Army, never did anything without a specific intent.

Into marching formation

At midday, 25 July, the order ‘Preparace’ came — prepare to march out. We were on high alert until 10 o’clock the following morning and thus missed out on the actual crossing — we had to content ourselves by hearing about it.

Naturally, during the time spent in ‘Preparace’ rumours were flying; all sorts of speculations and conjectures were made. The batallion staff remained silent. Like bats out of hell, the motorised dispatches continuously delivered messages to the staff, the chief of staff, Hoffmann [1], had changed into full combat gear; an old uniform and the largest revolver I had ever seen.

The atmosphere was cheerful although we were slightly nervous; by now, we all knew what lay ahead. The comrades sat around in small groups talking and singing, enjoying the glorious Spanish wine. A few men were writing to their families and girlfriends. By night, the kitchen was ordered to pack up, however, as far as we were concerned, there were no orders.

Not until 10 am the following day, the order was issued. The armed combat vehicles arrived and we rolled away shouting with joy. Finally, the long and boring instruction days had come to an end. It was time for the fascists to face the music. One of the men wanted a sabre so he could turn the Moroccans into crullers.

At the Ebro

Within an hour’s drive, we reached the Ebro and stopped in the city of Vino del Ebro [2]. It was complete destroyed. For six moths, the city had been targeted by fascist flying bombs and grenades. The streets were torn up. Torn light- and telephone cables were hanging down the walls. Of course the city had been evacuated on the orders of the government, even though it is located three kilometers from the Ebro.

Later on, in the city of Asco, located on the riverbank of Ebro on the fascist side, I saw that they used the front houses as machine-gun positions. These were the only houses that were disturbed by the war, in the rest of the city, life went on as usual; shops were open for business and so forth. The population trusted the Republicans.

We had to evacuate all civilians within a radius of six kilometers from the front, and even that wasn’t enough, as later testified by the horrible bombing of Barcelona and other cities.

We reached the river and were immediately put to work — carrying the wounded! Goodbye, all my dreams of pummelling the fascists. For the next couples of days, we only met wounded fascist, who, I might add, received the same treatment as we did. After all, the fascist usually shoot wounded Internationals.

Spaniards and Scandinavians from the Martin Andersen Nexø company resting after the crossing of the Ebro

The other bank

We were ordered to clear the other river bank of wounded and marched off four men on each stretcher. Across the Ebro, a provisional pontoon bridge had been built which we had to cross.Half-way across the bridge, the bombers came. On the bank, a couple of comrades burying the dead gave the alarm, but it was too late, we didn’t have time to cross the bridge and threw ourselves face down on the bridge. Then the bombs came; whistling and shrieking and ultimately, a thunderous blast that made shrapnel and debris whizz over our shoulders.

The river was thoroughly stirred up threatening the bridge to break loose — But that was all, nobody was injured and we went on as soon as it was over, soaked and trembling we went on — it was our baptism of fire.

On the opposite river bank we met ‘Spids’ alias Harald Nielsen [3] on his way to the hospital. He gave us the first news: the Danish Sergeant Kaj Jensen from Frederiksberg [4] was dead, hit by two bullets to his chest. Furthermore, my best friend, sanitarian Viggo Petersen had been killed by a headshot. We were deeply moved by these two messages; two brave comrades had lost their lives to conquer fascism.

Life goes on

We were not given much time to think about it, though. We worked non-stop. There was an unrelenting amount of wounded men to be transported to the doctor. In spite of grenades flying around our heads, we carried out our work with only two left wounded that day.

We could settle for the night knowing that we had done a good job for our cause. The desire to continue to do so had not diminished in the days that followed. Despite hunger, grief and lice, we carried on with high spirits.

Notes:

[1] Heinz Hoffmann

[2] The name of the city to which Viggo is referring, is actually Vinebre. In Catalan, the river Ebro is called ‘Ebre’ and the Catalan word for wine is ‘vi’. Maybe this is the reason why Viggo thought that the name of the city was Vino Ebro.

[3] You can read about Harald Nielsen in the article Four Danes in the Spanish Civil War.

[4] Independent municipality, part of the Capital Region of Denmark.

The battle of the Ebro was the largest, longest and bloodiest battle of the entire civil war. The two armies suffered a total of around 130,000 casualties in the months from July to November 1938.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.