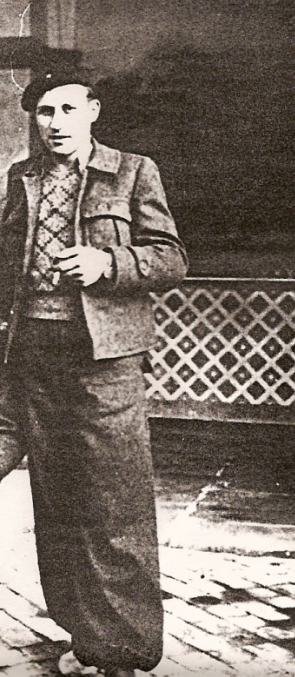

Wolfgang (‘Wolf’) Hoffmann

| SPANISHSKY.DK 10 MARCH 2019 |

Wolfgang Hoffmann – an anti-fascist sailor from Vienna

(Born 25. May 1912 in Vienna, died in March 11. 1942 in Camp of Gross Rosen)

By Allan Christiansen

Towards new horizons

Wolfgang Hoffmann was the seventeen-year-old son of a well-to-do Viennese lawyer. Sometime during the summer of 1929, he made up his mind to leave his home and his affluent circumstances – to find his fortune.

His decision disturbed his parents a great deal. In particular, his mother was deeply hurt. She used to sit for hours beside the window – waiting for him to return. She could not understand why her boy, who had enjoyed plenty of everything at home, had felt the urge to give it all up and wander the world.

But Wolf was inspired by a spirit of adventure. He wrote from Leipzig, asking for money and explained that he intended to travel on to Hamburg, look for a ship and become a sailor. His father could not dissuade him – and so used his influence to recommend him to an Austrian shipping company in Hamburg – and they agreed to employ Wolf as ship-boy on board the Steiermark. This ship was a tiny and hardly sea-worthy boat, which used to crawl along the Norwegian coast, up and down to the Polar and Baltic Sea. This is where Wolfgang started his career as a sailor.

It may sound strange that this rather spoilt boy, who had been brought up in a comfortable, bourgeois home, in a country far away from the sea – now found fulfilment in the unexpected adversities of his new pursuit. He tackled the hard work with enthusiasm, learned the Dutch dialect of the sailors, adjusted to the food, lack of sleep, sea-sickness and teasing of his mates. He matured. He became tough, strong and confident.

At Christmastime, he visited his parents in Vienna. His mother’s entire provision of rum was promptly consumed! But his parents were glad that he obviously found much pleasure in his job.

He returned to Hamburg, changed to a better boat, was promoted and now followed the route Danzig–Hamburg–Trondheim. During the following months, he sailed along the Norwegian and German North Sea coasts. He saw the beautiful Fjords and wrote enthusiastic letters about his experiences.

The Depression and Wolfgang’s political awakening

In the course of the 1930s, after the New York stockmarket crash, more and more people lost their jobs all over Europe. Families became poorer. They could no longer afford anything above the minimum. Even food had to be cut. All shipping was blocked. The ports were closed. Sailors remained onshore. They sat in taverns and discussed the causes of this situation.

Wolfgang had been caught by the crisis in Danzig, in 1932. Along with many thousands of German sailors, he lined up every morning at the door of the employment office, but no ships weighed anchor. Sailors discussed the reasons for this contradictory situation – when there were plenty of goods, but very few had the means to buy them. The working class lived in misery, and there was no hope of change.

The communists gave them an answer: this disastrous situation was caused by the capitalists! Communist speakers inspired hope in the working class. A previous revolution was crushed in 1919. They believed that a new revolution would provide them with employment and prospects for the future. Wolfgang started reading communist literature and became more and more convinced by the arguments of the Communist Party. There was one only possible answer to this unjust capitalist society: the means of production had to be controlled by the working class. He joined the Revolutionary Trade Opposition (RGO), and listened to the speakers at rallies held for unemployed seamen.

Thus passed several weeks of waiting in vain for relief and re-employment. The port of Danzig remained closed. Wolf decided to return to Vienna. Once back home, he joined the Communist Party, which, since the 1920s, had had some influence on the Austrian workers. They were intrigued by the pseudo-revolutionary phraseology of the leaders, in particular that of Otto Bauer. Wolf was less than 20 years old, but he had experienced three years of hard physical labour – and he knew what the life of a worker was like. The communists explained the inefficiency of the reforms, which were propagated by the social democrats, and they called for violent protests and strikes.

Actions, counter-actions, prison and concentration camp

In 1933, at Christmas, when people were unable to afford the customary celebrations, the party decided to organise a hunger rally at a central market in a workers’ quarter. Wolf was to be the speaker.

He wrapped a large stone in gift paper, as a disguise and smashed the front window of a shop advertising geese for Christmas dinner! He grabbed a few of the birds and threw them to passers-by. The Police caught him. He was accused of robbery and sentenced to three months in prison. The judge did not bother to explore the motivation behind this robbery, which was committed by a young man of wealthy background.

Meanwhile, the political situation had become more violent; the government of chancellor Dollfuss mobilised police and private paramilitary groups against the workers’ organisations. On 12. February 1934, bloody fighting started in Linz and then spread to Vienna and other large cities. After four days of tough battles, the leftist defenders of democratic loyalty were defeated and almost two hundred of them lay dead in the streets. Nine people were sentenced to death by hanging.

While his comrades fought on the side of the Schutzbund against the fascist government, Wolf was still in jail. When he came out, he was transferred to the concentration camp at Woellersdorf, used by the fascist regime to keep their numerous enemies under control. He was freed in the summer of 1934. Once again, he tried to find a job – and failed.

Spain

July 1936, the fascist generals in Spain started their uprising against the republican government which had arisen out of the February elections. In order to oppose this, a worldwide solidarity movement was formed to defend the Spanish Republic against General Francisco Franco and his fascist supporters, Hitler and Mussolini.

In November 1936, Wolf was among the first international volunteers, who defended Madrid against the fascist aggressors, along with Hans Beimler and many more German, Austrian and International ‘Brigadistas’. In the course of the Spanish Civil War, he participated in many battles – in Teruel, Brunete, Jarama and, in July 1938, on the Ebro. He was wounded and subsequently evacuated to France, together with hundreds of veterans of the International Brigades.

At this point in his life, he was able to enjoy a short, happy time with his wife and son, in Brussels. This pleasant interlude ended abruptly with the German invasion of Belgium and Holland in May 1940. The Belgian authorities panicked. They detained all German-speaking people and deported them to France.

After the capitulation of France, in June 1940, the Gestapo obtained control of the detainees in southern France and arrested those they considered enemies. Wolf was sent to Vienna, where he was accused of high treason, a charge of which he was acquitted. But, instead of being released, he was sent to the Dachau Concentration Camp. Shortly afterwards, he was transferred to the Extermination Camp of Gross Rosen, in Silesia (today in Poland).

On 11. March 1942, he died, not yet 30 years old ‘from heart deficiency’, as stated in the records. His name is written on a simple plaque of marble, which commemorates five members of the International Brigades, who were victims of Nazi brutality, killed in the Camp of Gross Rosen. The traces of this sombre place are preserved as a memorial, today protected by the Polish state.

Obituary (in German) for Thomas Hoffmann, Wolfgang Hoffmann’s son, who, as his father, was an anti-fascist and communist.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.