Edgar André – A Brief Biography

| SPANISHSKY.DK 30 APRIL 2021 |

Better to die on your feet than live on your knees

All fights give birth to heroes — brave men and women who risk their lives for the common good. Persons from whom we can take example whether or not their fight was successful. They are woven into the fabric of the culture in which we insert ourselves

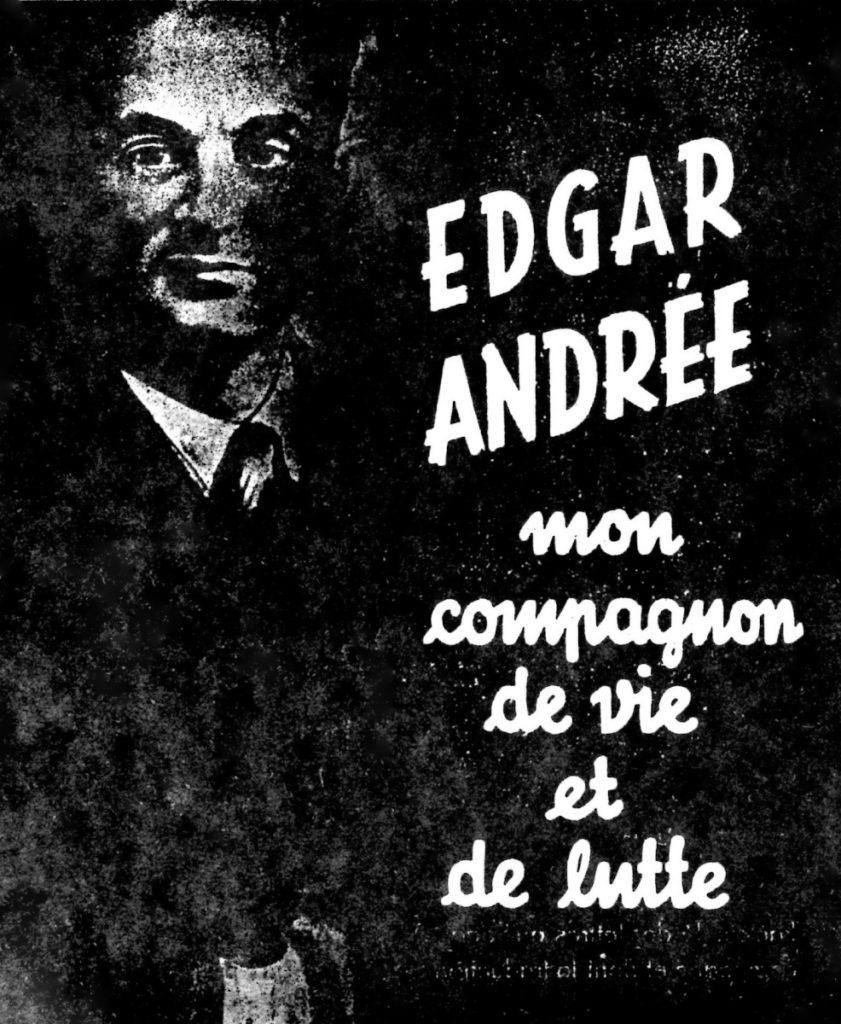

One such person is Edgar André. Although subjected to neglect in his childhood, he developed into a highly empathetic man who placed himself on the side of the working-class people. He was courageous and never wavered in his commitment. His integrity was second to none, and he was well-liked among the unemployed and the workers and feared by his enemies.

By Friends of the XI International Brigade/Revision and translation editing by Maria Busch

Beginnings

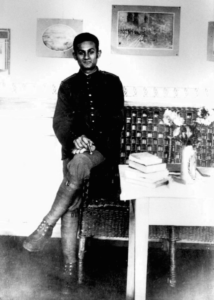

Edgar Josef André [1] was born 1 January 1894 in Aachen in the Rhine Province of Prussia. His father died when he was 5 years old. Edgar’s ailing mother struggled to support three children on her own, so they were sent to live with some relatives in Liège in Belgium, though Edgar spent some time in an orphanage. After having finished highschool, he started as an apprentice to a bookseller.

Edgar loved books more than anything. Even when he was unemployed, he often spent his last penny buying a new book that had caught his attention. Already as a teenager, he became interested in political literature. Before long, he positioned himself politically and joined the Parti Socialiste belge, PSB (Belgian Socialist Party). Within two years he was appointed secretary of the Socialist Workers Youth in Brussels.

After the end of World War I, he settled in Koblenz and in 1922 moved to Hamburg.

At this point in his life, Edgar was a social-democrat and worked as a casual labourer in construction or as a longshoreman in the port of Hamburg. He joined both unions — the Building Workers’ Alliance and the Transport Workers’ Alliance.

The gift

Edgar had a special gift. He was a captivating and spirited speaker. Effortlessly being able to relate to their living conditions and everyday life, he knew how to inspire his labour brothers and sisters and make them realise the necessity of a common struggle.

To those who knew Edgar, it was not surprising when the unemployed labour force in Hamburg elected him chairperson of their unemployed organisation. Edgar was so well-liked and popular among the workers that even the middle-class press referred to Edgar André as ‘The King of the unemployed’.

However, his views and the views of the right-wing leaders of the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany) could no longer be reconciled. He experienced a deep and unbridgeable divide between the privations of working-class life and the actions of the right-wing leaders of the party, which left him no choice—by the end of 1922, he left the SPD and on 1 January 1923 Edgar André became a member of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, KPD (The Communist Party of Germany).

Ernst Thälmann

He soon forged friendly ties with Ernst Thälmann, chair of the local group of the Vereinigte Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, VKPD (the Unified Communist Party of Germany) in Hamburg. Thälmann appreciated Edgar’s gift of giving speeches and his positive influence on and tight connection to the working-class people.

The communists—including Thälmann—nicknamed Edgar ‘de Swatte’ (Blacky) because of the colour of his skin and hair. Edgar, on the other hand, nicknamed Ernst Thälmann ‘The Boss’.

Hard times

The Weimar Republic of 1923 was facing enormous economic and political problems, causing unrest and strikes on which the Republic came down hard. During this tumultuous time, Edgar was arrested while demonstrating and spent four months in prison.

When the Roter Frontkämpferbund, RFB (Alliance of Red Front-Fighters) was founded in 1924, Edgar André became chairman of the Wasserkante (‘Waterfront’) district. Here too, his speciel gift was a big asset, and he powerfully involved the unorganised young people and social-democratic workers in the RFB repelling of fascist attacks. In Hamburg alone, the RFB soon counted thousands of members.

Besides his relentless work for the RFB, Edgar André was a member of the KPD Council in Wasserkante.

A dedicated internationalist, Edgar André was steadfast in his conviction that any worker’s struggle was his struggle. A primary example of this was the The Sacco and Vanzetti case from 1927: Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian immigrant anarchist workers, were controversially convicted of robbery and murder and sentenced to death in Massachusetts, the United States. Edgar took part in the worldwide support of their innocence and the attempts to get them acquitted—but to no avail. 23 August 1927 just past midnight, Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in the electric chair [2].

Following the execution, the rapidly growing transnational networks launched protest actions around the world. In Hamburg, the protesters rallied in front of the US-Consulate. The Consulate was located in the in the ‘neutral zone’ around the parliament, in which demonstrations are not allowed. That didn’t seem to worry Edgar André and the later to become Brigadist in Spain, Erich ‘Vatti’ Hoffmann, who marched at the very front of the demonstration. The police opened fire; one worker died and 30 others were seriously injured.

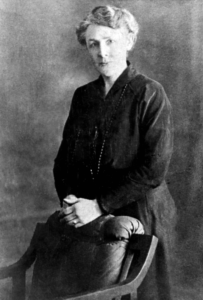

Amidst these troubled times, Edgar established a firm relationship with his female party comrade Martha Berg, which lasted until his untimely death.

Martha and Edgar were cut from the same cloth; always helpful and comradely, ready to put the interests of their class before their own and lively and open-minded.

In February 1928, Edgar André and 26 other communist delegates were elected into the Hamburger Bürgerschaft (Hamburg City Parliament) — a position he kept until 1933. The saying goes that power brings out your true self; Edgar remained faithful to his ideals, and he donated most of his salary to the party treasury.

Political actions 1929

Although the International Workers’ Day was banned in Berlin in 1929, the KPD arranged their own May Day demonstration. Almost instantly, the demonstrators were attacked by policemen using firearms. What started as a protest escalated into a three-day riot during which the police killed 33 people, injured around 200 and arrested over 1200. The RFB took part in the riot—for posterity known as Blutmai (‘Bloody May’)—and was therefore banned.

A great demonstration was called against the ban of the RFB 27 October 1929 in Hamburg. It started in the morning with a rally in the city centre. In the afternoon, more than 1000 RFB fighters in civilian clothes assembled in a sidestreet of Barmbek—a working-class district of Hamburg. In 1925 Ernst Thälmann had referred to this district as ‘immortal’ because of its heroic role in the 1923 Hamburg uprising.

Just a few moments before the demonstration started, the fighters handed over their coats to the women present and marched through a crowd of amazed passers-by in the RFB uniform. The vanguard was composed of Ernst Thälmann, Edgar André and Erich Hoffmann, along with other comrades. Eventually, Ernst Thälmann climbed up a lamppost and held a speech against the ban of the RFB.

International workers’ conferences

The first international conference of coloured workers took place in Hamburg 7 July 1930. The intention was to recruit those for the common fight who worked under the worst working conditions.

Edgar André was an unrelenting organiser and passionate propagandist, and his articles were published in the French trade union magazine La Vie Ouvrière among others. He also used his perfect French and his knowledge of Marxist-Leninist theory to work actively as an instructor and propagandist with the International of Seamen and Harbour Workers.

One of his duties was to establish and maintain contact with the seafarers and dockers in the cities of Antwerp, Le Havre, Marseille, Leningrad and throughout Spain and China.

In 1932 Edgar could report to his party that an organisation similar to the RFB had been founded in France.

He also took part in the organisation of the Antifaschistische Aktion (‘Antifascist Action‘) congress on 26 June 1932 in Hamburg with an assembly of 1719 delegates, 270 of whom were social-democrats. The Antifascist Action made the appeal to the members of the SPD, the Sozialistischer Jugend-Verband Deutschlands (‘Socialist Youth League‘) and the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold (‘Black, Red, Gold Banner of the Reich’) for the joining of all workers in the Workers’ United Front.

The seat of the KPD leadership, Berlin 1932BundesarchivLicense

Because of his fearless commitment to the interest of their class, his untainted morality and unselfishness, the industrial workers of Hamburg, the dockers and farm workers on the fields of Schleswig-Holstein always spoke highly of Edgar André.

Besides his trade union and political work and actions, Edgar was attending Nazi meetings to expose the supporters of the party.

The Nazis hated Edgar André

Edgar André had gradually become a thorn in the side of the Nazis. Karl Kaufmann, Nazi-Gauleiter (District Leader) and later to become Reichsstatthalter (‘Reich Governor’) of Hamburg, ordered his henchmen to kill Edgar André.

The assassination attempt was carried out 15 March 1931: the three assassins had been informed of Edgar André’s whereabouts. They followed him as he left his meeting and got on a bus home. They forced their way into the bus and opened fire. One of them confronted the intended victim and said: ‘You are André’ and shot him. An accompanying comrade was shot in the head and subsequently lost an eye, and another passenger was shot in the thigh. The assassins, however, were totally unaware that on this particular evening, Edgar had asked one of his comrades, Ernst Henning, to replace him at the meeting.

The three men who took part in the liquidation were caught and brought to trial. Only two of them were sentenced — to seven and six years, respectively. The view taken by the judge was that the murder of Ernst Henning was committed in ‘the heat of the moment’ and dropped the charges of first-degree murder.

On 21 May 1931, Ernst Henning was buried. Edgar André led the enormous funeral procession of about 35.000 people. The police took advantage of the existing demonstration ban and opened fire on the procession. One worker was killed and three others wounded. This was just one example of the brutal conduct of the social-democratic Weimar Republic police force. A conduct that reflected the political agenda of the social-democratic regime of Germany.

One social-democratic delegate in the Hamburg parliament, Gustav Dahrendorf, was quoted by the social-democratic newspaper Hamburger Echo as saying: ‘Better 10 Nazis than one communist in the council’. The same Gustav Dahrendorf was arrested on the 24 March 1933 and held in ‘protective custody’ for a few days only to be taken into custody again in May 1933 and interned for three months in the Fuhlsbüttel Concentration Camp where he was severely tortured by the Nazis. 20 October 1944 he was sentenced to seven years in prison and sent to Brandenburg-Görden Prison to serve his sentence [3]. Depending on one’s point of view, it is either the ironies of life or poetic justice.

Wanting to protect himself from new attacks on his life, Edgar applied for a firearms permit which was rejected by the social-democratic police chief. Edgar therefore got a well-trained guardian dog — a German Shepherd called Ajax. Ajax fiercely protected Edgar and attacked everything and everyone wearing a swastika. He even destroyed the nazi symbol decorated silk ribbons of the wreaths laid down on Nazi monuments.

The Nazis constantly lay in wait for Edgar seeking an opportunity to kill him. Once a gang of SA men surrounded his housing block before forcing their way to his apartment. As the assailants stormed in, Edgar was talking to himself in a loud voice and made it appear as if a handful of men were handing him fire arms. In the darkness, the Brownshirts could only see his shadow and it looked like he had a revolver in his hand. Edgar André asked them to come closer and then shouted: ‘Out of my house or I’ll shoot!’. The SA men fled. In his hand Edgar had a pipe turned upside down.

1933—The Nazis seize power

The Nazis used the Reichstag Fire 27. February 1933 to seize absolute power. That very night, from a list already prepared, the Nazis started a wild hunt on communists and social-democrats arresting around 4,000 people who were subsequently detained indefinitely and tortured by the SA [4].

After German President Paul von Hindenburg had handed over the power to Hitler on 30 January 1933, Willi Bredel advised Edgar André to duck under the radar for a while. Edgar refused, explaining ‘I’m needed in the district, especially with the sailors of the fish trawlers in Cuxhaven‘ — one of the areas for which he was responsible.

It is, in effect, difficult to determine why Edgar did not listen to Bredel. Had Edgar become careless? Did he underestimate the danger?

5 March 1933, on the train back from Cuxhaven, Edgar André was arrested. At this very moment, a period of suffering began that was to last three and a half years.

Imprisonment

Over the coming years, the nazis subjected Edgar to unbearable torture to break his resistance. Ranging from being humiliated to beaten into unconsciousness, no method of torture was left out. Every seventh to tenth day, his life partner Martha had to pick up his bloody clothes, wash and return them.

Eventually Edgar’s body was so mutilated from the constant torture that the nazis placed him in a waterbed so he could recover adequately before being subjected to another round of torture. We will spare you from further details about these atrocities.

Karl Kaufmann was present at one of the torture sessions. In passing, it should be noted that after the war, Mr Kaufmann lived the quiet life of a pensioner in a villa in Hamburg until he passed away of natural causes.

Despite the prolonged, systematic and detrimental torture, the Nazis could not break Edgar André.

After being released, one comrade recalled an encounter with Edgar in prison:

‘There was Edgar André walking on crutches. The other comrades recognised him right away, and he seemed to know many of them. Suddenly Edgar shouted: “Straighten up!” When he realised the prisoners followed his command, he looked intently at them and gratefully said: “Thank you comrades, I can see, that you have forgotten nothing”. On this day there was no way the torturers could get any information out of us.’

Edgar André knew of a police informant outside the prison. One day in March 1933, for once unguarded, he shouted loudly to his inmates in the prison compound: ‘Attention comrades, attention comrades, this is Edgar André speaking. I am telling you that Willi Kaiser is a police informant!’ Many of the prisoners knew the informant and were now warned.

A first attempt to free Edgar André in the summer of 1933 failed. Some of his comrades searched for him in the Hamburg hospital, but to no avail. In 1934, the KPD devised a plan to free Fiete Schulze and Edgar André. This second attempt was equally unsuccessful as the police got word of the plan from a police informant.

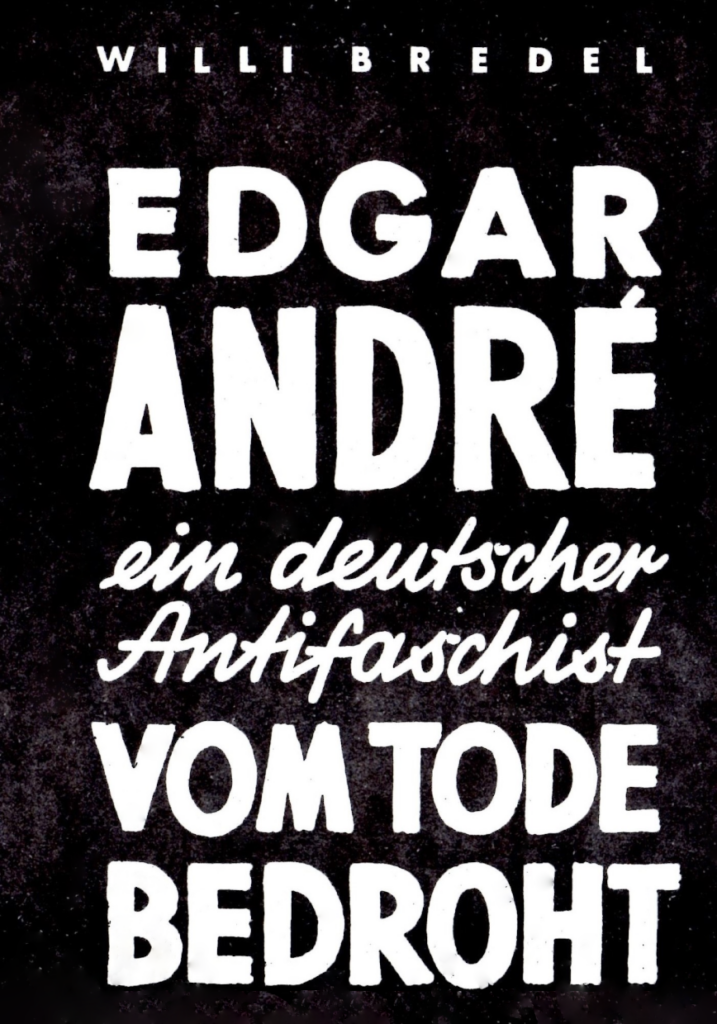

Poster by Willi Bredel, Moscow, 1936: ‘Willi Bredel, Edgar André: a German anti-fascist threatened with death’

Trial

The trial against Edgar André began on 4 May 1936 — more than 3 years after he was arrested. As could be expected, it was nothing more than a nazi mock trial.

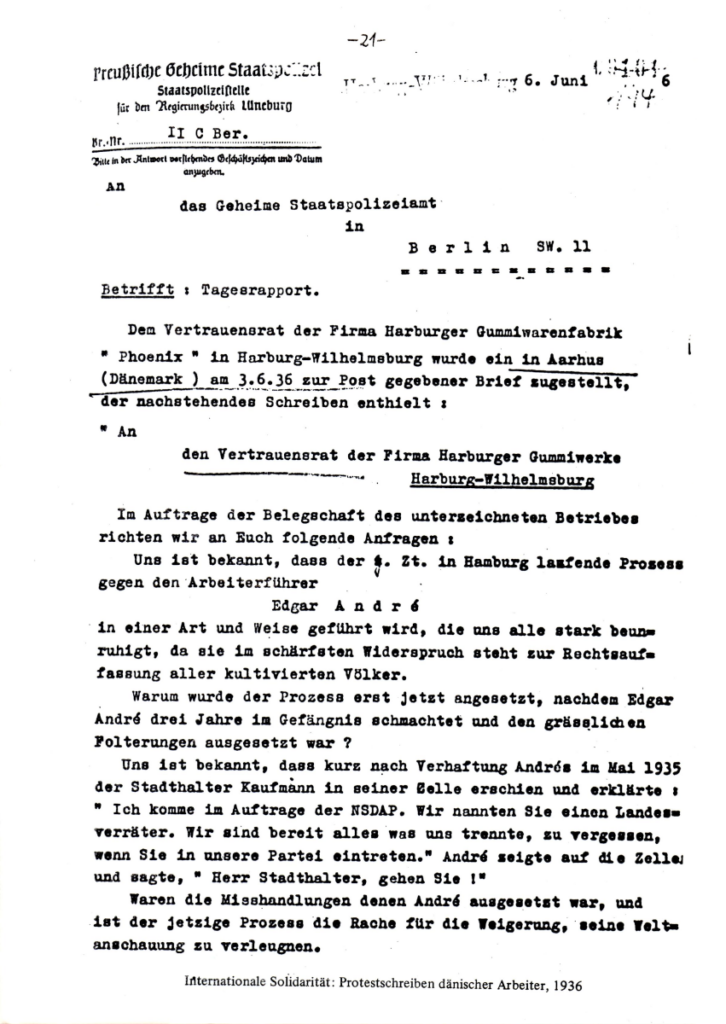

While the trial lasted, an overwhelming international protest movement demanded the release of Edgar André — thousands of telegrams and letters from many countries, among them Denmark, were sent to Hitler.

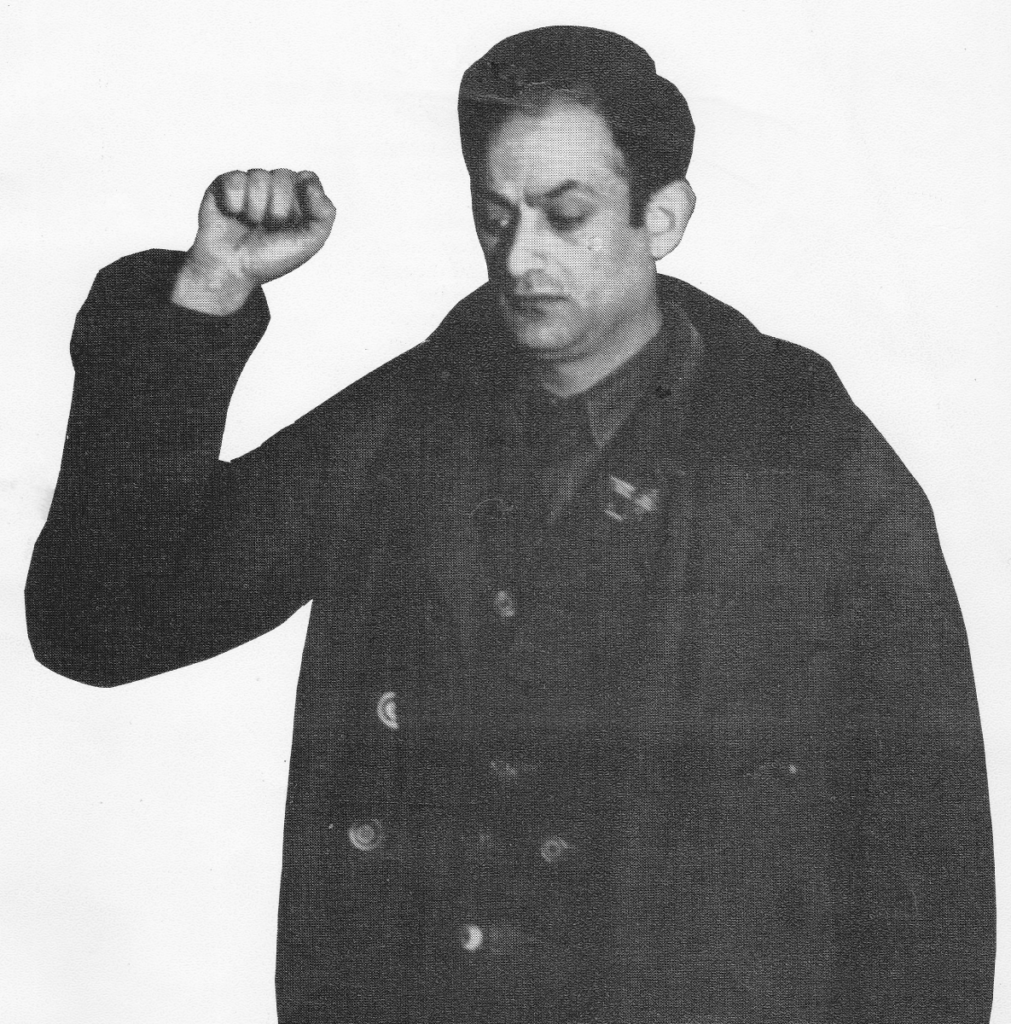

The French socialist newspaper Le Populaire reported about the trial: ‘They are demanding the executioner’s axe for Edgar André, the inventor of the greeting with the fist. André is a working-class hero and an invincible union fighter’.

In New York harbour the New York Action-Committee passed out leaflets on the German ship Bremen calling for the release of Edgar André and halted weapons deliveries to the Franco-Fascists. At the bottom of the leaflet it said: ‘Hands off Spain! Free Edgar André, Lawrence Simpson, Ernst Thälmann and thousands of imprisoned and tortured opponents of war!’

Edgar André faced several charges — including that of murder. There was no evidence of his guilt, and nothing suggests that he advocated murder. He wholeheartedly supported the KPD stance on individual terror: ‘The communists oppose any form of individual terror. Even when the call for violent actions in our own ranks became louder and louder because of the rising terror of the Nazis, the party went against it. The only solution is class struggle. Individual terror will only serve the bourgeoisie and the provocateurs’ incitement to hatred’.

The last day of his trial, 1 June 1936, Edgar André said his closing remarks and addressed the judges: ‘Your honour is not my honour, we are divided by ideology, by class. There is an insurmountable abyss between us. Should you decide to do the unfathomable and condemn an innocent fighter to the block, I’m ready to bear that burden. I don’t want mercy! I have lived as a fighter and I will die a fighter with “Long live communism!” as the last words on my lips’. Friday 10 July 1936, he was sentenced to death by beheading.

Execution

4 November 1936, six o’clock in the morning, Edgar André was executed with an axe. His lawyer later described his last minutes: ‘Edgar André walked the 12 meters to the execution site upright and alone. With only a few seconds left, his mighty voice suddenly echoed through the prison compound: “Long live communism! Down with the mass murderer Adolf Hitler!”. Then Edgar André died.’

The Spanish Civil War

His name was immortalised during the Spanish Civil War, when the first battalion of the International Brigades was named after him. The Edgar André Battalion fought on the front line in Madrid in November 1936, helping drive back the Franco fascists.

The Edgar André Battalion (photo cropped)BundesarchivLicense

Sources and notes:

[1] On his birth certificate, it says Etkar. However, he himself changed his first name to Edgar in the early 1920s. The two different names often give rise to confusion. He entered history and literature as Edgar. We respect his will and call him Edgar.

[2] Sources and additional reading: Sacco and Vanzetti executed, history.com, 20 August 2020; Sacco and Vanzetti – American anarchists, brittanica.com (11 February 2021); Frankfurter, Felix: The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti, The Atlantic, Issue March 1927; McGirr, Lisa: The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti: A Global History, The Journal of American History, Vol. 93, No. 4 (March 2007), pp. 1085-1115; Sacco and Vanzetti, en.wikipedia.org (11 February 2021).

[3] Gustav Dahrendorf, de.wikipedia.org (11 February 2021); Gustav Dahrendorf, Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand (11 February 2021).

[4] Boissoneault, Lorraine: The True Story of the Reichstag Fire and the Nazi Rise to Power, smithsonianmag.com, 21 February 2017; Mage, John and Michael E. Tigar: The Reichstag Fire Trial, 1933-2008: The Production of Law and History, Monthly Review – An Independent Socialist Magazine, 1 March 2007.

The opening quotation is attributed to the Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata (1879–1919).

Thanks:

Unless otherwise indicated, the historical photos are from the Ernst Thälmann Memorial in Hamburg. We thank them for the permission to use them in this article. The memorial which is open to the public, preserves the legacy of the German and international labour movement’s struggle.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.